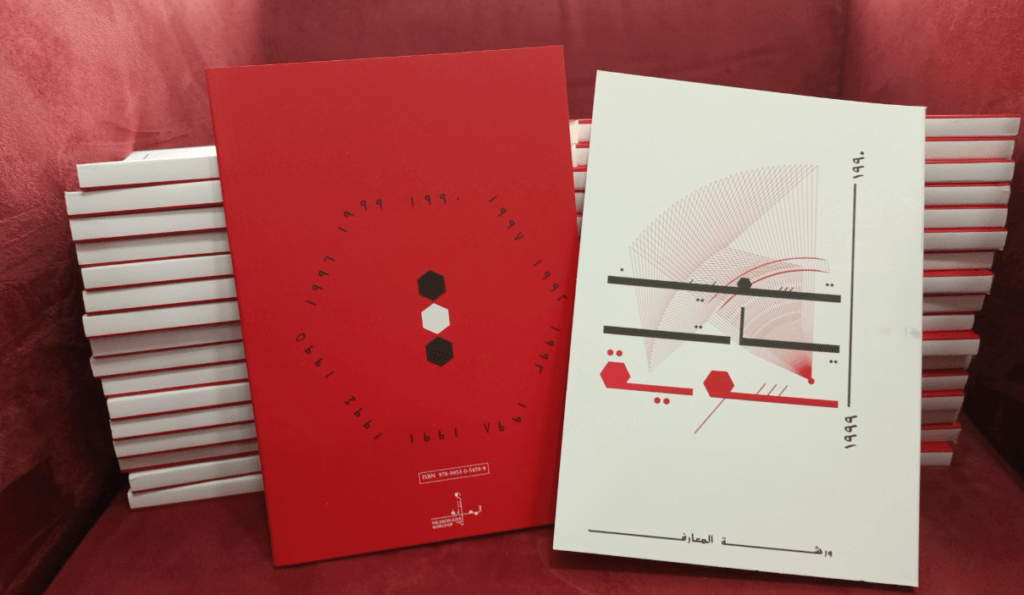

The framework, by Deema Kaedbey

In an interview that KW did with Jean Said Makdisi in 2017, she called on “Arab feminists” to “do our homework” and turn towards our histories as a way to explore the layers of our present and our tomorrow.[1] In this publication, Jean’s chapter on activists and feminists in the 1990s repeats the same message: “we [have] a great deal of homework to do on our past.” There is so much to learn, so much to be surprised by, necessary confrontations to have and hard questions to ask, many of them to ourselves. But ultimately, this past is the vital ground to work with and expand on. Throughout we have been aware of taking an approach to the past as moving and multi-layered. And we worked within a framework that is welcoming of multiplicities of past stories and futures.

In this publication, our interest was also multi-fold: we recognized the importance of learning about the feminist and women’s movements during that decade, in its varied strands, concerns and strategies. More than one chapter in this book will make that distinction between the feminist and women’s (or “the woman’s”) movement. Some feminists also tried to create a genealogy for us today, as Fatima Moussawi notes in her impressive exploration of the feminist movement in 90s Lebanon. At the same time, we wanted to learn about the context, to take a closer look at socio-economic and cultural topics during the 1990s, with feminist eyes that disrupt oppressive and simplistic gendered assumptions.

And as our attention turned to the feminist movement in the 1990s, we were aware that we are often asking questions more relevant to us today, that we knew were not deemed important as at that time.

Therefore, since the inception of this publication, we were excited by the possibilities of connecting across generations and communities and across different frames of references to talk about feminist issues. We wanted this publication to acknowledge and appreciate the long and hard struggles of feminists and women organizers in the 1990s. And equally, we were moved by critiques and questions for organizers about this period. We wanted to know how a movement grows and changes, how are issues marginalized during a period, and how do they start to gain momentum? How do we build on each other’s work? We also sought to understand how the scene that we came into at the beginning of the 21st century came to be; why did many of us in the early 21st century feel that we were creating and talking about issues for the first time, if these topics were already being discussed since the nineties? These were questions to ask both of our younger selves and veteran feminists.

Out of all the periods in Lebanon, why did we choose the 1990s? The idea of this publication was first planted by a genius perception of KW’s co-founder (and co-director until 2020), Sara Abou Ghazal, towards the end of 2019 and early 2020. Sara perceived that in 2020 we will not be able to organize as we have always done (that was even before we heard of covid), and that we should direct KW’s efforts towards a publication that went to the heart of KW’s mission: to remember, connect, and produce accessible feminist content and history.

And as the weeks and first months of 2020 unfolded, the idea matured to settle upon the 1990s.

The 90s was a decade that was already being evoked by feminists, especially that 2020 marked the 25th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women, or the Beijing conference. You will read about the significance of this conference for feminists in Lebanon in many a chapter of this book. Following this monumental gathering, more feminist and women’s organizations were established in order to work on issues that found new life and new energy after Beijing, propelling the age of the NGOization of the feminist movement. This shift was important for us to revisit, while also considering the larger socio-economic changes taking place. And did these changes contribute to a certain reification of the boundaries of a movement, insulating it sometimes from other social and political movements? The 1990s was also being regularly remembered by activists, especially during and after the October 17 uprising, as the decade that launched economic and political “Harirism,” ultimately leading to the collapse that is still unfolding in 2021, destroying lives and livelihoods. The 1990s of course saw the official end of the civil war, but South Lebanon was still occupied by Israel, and Lebanon was still under Syrian Baathist control. What was that like for women, for feminists? The 1990s was not too long ago, so that many of us still remember it, and many of the feminists and activists around us were active during that time; but it was long ago enough that young feminists today are not familiar with it.[2]

“آفة حارتنا النسيان”—“Forgetfuless is the plague of our alley,” Sara invoked Naguib Mahfouz’s words in Children of the Alley (Awlad Haritna) back in 2015, in a Sawt al Niswa essay, to describe a recurring pattern of forgetting our histories among feminists, and falling into “the trap of renewal that forgets and retracts instead of bridging and building on.[3] Indeed, even though the 90s is not of a distant past, it was still startling to realize how much so many of us in our feminist alley ( حارتنا النسوية ) had forgotten. We know so little of the stories of a generation that is still around us, and we have not had enough opportunities to ask, tell and listen to these stories collectively. It is sad to consider that the names of so many feminists and women’s rights activists who did phenomenal work are not well-remembered today, even though we are building on what they have fought to establish. At the same time, this remembering and acknowledgement of veteran and ancestor feminists does not need to be cast in an aura of perfection. We can love and appreciate while seeing the failings and mistakes.

This publication intends to move a few steps towards healing and tending to the plague of forgetting. In the context of the nineties, we acknowledge that many women and feminists at the end of the war felt that they needed to not remember in order to be able to proceed and push through with their lives, and with work that was violently halted for 15 years.[4] On the other hand, despite all the talk of collective forgetting in Lebanon, this publication also reminds us that some communities and groups cannot afford to forget and move on (as both Wadad Halawani and Leila Al Ali remind us in chapters 10 and 11 respectively). And often these communities get attacked for speaking out, for not forgetting. We acknowledge too that there are so many women who will remain nameless and whose contribution will not be highlighted– Sintia Issa (chapter 14) and Lina Abou Habib (chapter 16) take note of this in their essays in this publication. There are many reasons why so many feminists and women are not remembered: out of fear, out of neglect, out of inability to document; it may be because sometimes we often remember more easily those who are/were in the limelight, or because some people do not want to take center stage and just want to do their work quietly. For whatever reason, this publication also honors these individuals and their contributions.

Remembering, grounding, connecting, storytelling and producing knowledges have always felt like spiritual-intellectual work; political too in that it is meant to create shifts in our lives, in the stories we tell. It is also something I never fully leave and yet I still find myself constantly returning to.

This framework is what I am returning to in this publication: that any moment of feminist activism holds multiple pasts, is connected to multiple other contemporaneous issues and occurrences, and holds many possibilities that are moving towards us as we are moving towards them (Kaedbey, Sawt, 2015).[5] Of course, we may not be aware of these pasts or presents, or we may be intentionally trying to exclude or distance ourselves from them. However, my intention with this framework is to open to stories from different periods, and different perspectives. I suggest this framework as an alternative to the more linear and compartmentalized waves metaphor of thinking about the history of feminism.

Despite its usefulness, narrating the story of a movement in waves does not reflect the complexity of histories, the entanglement of narratives, perspectives, and temporalities (Kaedbey, WHR, forthcoming).[6] If we use waves as a way to mark the periods when a movement flourishes and gains momentum, we leave behind periods with less visible surge of activities, but where important work is still being done. And if waves are used to talk about major shifts in discourse and strategies, then I think we have more than four waves in Lebanon to pay attention to. Instead, we might observe that every 15-20 years—more or less— more evident changes begin to happen within a movement, perhaps as a new generation emerges. But that does not mean that other, and older, forms of organizing and discourse are not still present, even when they are not receiving as much attention (Kaedbey. WHR, forthcoming).

In whatever framing we want to tell our feminist histories, I believe in our collective feminist desire to narrate stories with more layers, more connections; and stories that recognize the shadows. Perhaps the timing of when these stories are told also matters. We are delving into this past at a time of massive changes, migrations, polarization and enemization, of surveillance and scrutinization and the reification of global power structures. These are times of isolation and many painful separations, but also of eerie global interconnections. It is clearly a period of immense povertization, not only economic, but also educational and cultural. This is a time when feminism is so needed because it pays attention to all the different layers of our existence: the inner, the interpersonal, the global, connecting different forms of violence and the many ways that individuals and communities resist. The feminism that we love and want is also attentive to how and why we got here and where we are going. And it is always curious to connect with other movements, other stories, to stay in the process of learning.

At the same time, in the spirit of a multi-fold approach that accepts contradictions, we also understood the usefulness of linearity and simplified/well-defined temporal, and geographic, constructions.[7] It is for this reason that we kept the focus on the 1990s, and on Lebanon. Still, Lebanon’s civil war years are embedded into the stories of the post-war, as much as 2020 is entangled into the act of remembering a bygone decade. Similarly, it is impossible to erase a transnational element in the telling of the stories of women and feminists residing in Lebanon.

We hope that you will find what you came looking for in the coming pages, in the stories this book holds. We are aware that there is always so much more ground to cover. In one of our meetings as we were bemoaning how certain topics and perspectives are not covered in this publication, Safaa reminded us that “if we were to cover everything, we would never finish.” And it made us think how, after many months of being immersed in this project, we still felt like there is so much more to learn. We are still just as curious and excited to know more. This is the work of continuing to expand our horizons, to grow deeper, more rigorous, but also more imaginative. This publication wants to reawaken our collective longing to listen and be listened to, to remember and openly share more of our stories.

Whenever the editorial team talked to the writers and researchers working on this book, we encouraged them to let the stories and the women’s voices come out. Stories and storytelling are at the core of KW’s work in the world, and they are the beating heart of this publication. Rooted in an intention to connect, intimately, to turn towards each other and learn from each other. And this, as you will read in the upcoming section, is what guided our process throughout this book.

The Journey, by Safaa T.[8]

When we were thinking about where to start, it became clear that there was a lot to do. We set out to compile all the information, writings and cultural productions that were published during or about that period. We read every research paper we could get our hands on that talked about the feminist movement in Lebanon in the nineties. We watched films that tackled gender themes, and drew up a list of feminist and women’s associations that were active during that period. We sometimes hear about actors and actresses who strive to embody the roles they are playing, which made us realize the necessity of retrieving as much information about that period as possible before creating this new incarnation of the research. That is why we circled back to nineties music and some of its artistic aesthetics; we read about the architecture of Beirut during that period, about its distorted reconstruction; and we explored literature, novels and theater. In addition, we discussed economics and neoliberalism, immigrant labor and the sponsorship system (kafala) during that decade, as well as women’s economic rights at the time. A lot of what began then is still happening today, which is why wanted to learn more about how we got here, in order to address the matter with more knowledge and depth.

But these different dimensions that we sought to explore required multiple, parallel and successive processes. Our first step was to put out a call for the submission of research papers on the designated topic, to select researchers who we can support more closely throughout their research and writing process. We chose Luna Dayekh’s proposal because it took into consideration different economic and social dimensions when reflecting on the narratives of women activists in the 90s. Soon after that first call, we issued a broader call for abstracts, which encouraged non-academic and contemplative writings, leaving writers the freedom to choose the issues they desire to tackle, as related to the topic “the nineties from a feminist perspective.” We were on the lookout for writings that critique and analyze political, economic and social issues, and for more intimate and experimental narratives.

This process was happening during July and August of 2020, in light of both a political and an economic collapse, with the spread of covid19 and then with the explosion of the Beirut port. Indeed, we wondered if people were ready to contemplate and write in these harrowing circumstances, while of course being aware that most of what we are experiencing today are repercussions of past decades, especially the nineties. We also knew that many individuals and groups had recently started thinking out loud about these temporal connections, especially after the popular uprising in 2019. For that reason, it was moving to receive this quantity and quality of submissions, whether they were abstracts on theatrical productions, music, and art, or on the feminist movement in the 1990s and the economic situation of women. There were also more intimate submissions depicting personal experiences lived by women and feminists during that period. What was interesting was seeing how the texts intertwined, and how many writers and activists brought up the same events, each of them presenting their own perspective and experience.

When we first read Azza Chararah Baydoun’s letter from her personal archive, which she submitted to be published, we felt profound enthusiasm with each paragraph we read. This was indeed a part of what we were looking for: to capture how and what feminists were thinking at that time, to understand how they interacted with the events that took place, and what part of those discussions didn’t reach us yet.

We also used oral history as a tool for communication and remembrance. Zeinab conducted an oral history interview over two sessions with T., a migrant worker who lives in Sidon. T. came from Sri Lanka to Lebanon in the nineties and still resides here today. Her story may be her own, but she shares the details of a life and of struggles common to thousands of migrant workers in Lebanon. And because we appreciate and acknowledge the importance of Al-Raida magazine and its role in feminist knowledge production since its creation, we contacted Myriam Sfeir, the current editor-in-chief of Al-Raida, who has been working there since the nineties. The oral history interview we conducted with Myriam gave us a lot of details about the events of that period, about Beirut in the nineties, and about the feminists she worked with. Zeinab and I also conducted an oral history interview with Wadad Halawani, who in our minds, represents a cause we wanted to tackle and talk about since we first started working on this publication. We have always known the “official” end of the war was very misleading. The violence was sustained years after, through structural forms of violence rather than as direct confrontations on the streets; amnesty was given for the war crimes, and the urge to return to “normal” life didn’t leave way for a transitional justice period.

After Zeinab completed the transcription of the oral history interviews, we selected the passages relevant to the 1990s and extracted them from the transcription, converting them into personal prose. As an editorial team, we edited the texts in a way that we believe keeps a balance between being easy to read while still being true to what was spoken. It wasn’t easy to write those testimonies in a colloquial language, due to the lack of rules and absence of a reliable framework for colloquial Arabic. Therefore, we tried as much as possible to mix the origins of the word in formal Arabic with the colloquial pronunciation, and we adopted various writing styles. As for the interview with Wadad Halawani, we recalled the most important parts of our conversation, and wrote about it in a text which includes some reflections on the issue of the missing people. At the same time as we were finalizing Wadad’s testimony, the families of the victims of the port explosion were on the street demanding justice and accountability.

In addition to research, writings and oral history interviews, we wanted to tackle topics related to the core of this project, notably: searching for lessons from that period by analyzing the methods of organizing used by Palestinian and Lebanese feminists and activists in various regions in Lebanon, learning more about the queer life before it became more politically organized, and highlighting the earliest voices of migrant workers who advocated for the rights of their communities. Therefore, we gathered a harmonious team of three brilliant researchers: Fatima Moussawi, Mariane Ghattas, and Sintia Issa.

While working on this book, one of the things we enjoyed most and benefited from was communicating with a large number of people, and making use of their experiences at every step. As one case in point, the process of peer reviewing the research papers was a beautiful and informative collective experience. We were lucky to be able to bring together an inspiring group of individuals from different academic, artistic and activist backgrounds to discuss the papers together and provide feedback that would be of help to the writers as they revised their papers.

As an editorial team, we were aware that some of the issues discussed were current feminist concerns, and we were also aware that the language we used and our editorial policy used reflect this moment that we are part of. We adopted, in our editorial policies, the use of the word “women” instead of “female/woman” to include women with different identities. In addition, we discussed the oft-used term “Lebanese woman” with the writers and researchers. We also expanded our field of vision when talking about women, asking how Palestinian, Syrian, Ethiopian, Sri Lankan and other women have contributed to deepening our feminist consciousness, and better understanding how they participated in shaping the feminist history of these countries, especially during the 1990s. In some of the chapters of this publication, we can see how these issues are not new: feminists held those same discussions in the nineties in order to break the discourse in which multiple issues are grouped under the title of “Lebanese woman.” A few chapters of this book shed light on the structural racism that undermines the attempts of the feminist movement to address issues more inclusively.

We knew from the beginning that we wanted the publication to be in Arabic, since at the core of our work was the desire to produce knowledge in Arabic and to ensure its accessibility. In fact, the lack of available resources prevents us from writing about ourselves and our history in our language. As we expected, we received some research papers in English. We thus worked on having them translated and edited with a feminist approach which conserves the concepts and spirit of the original texts. But we were also pleased with receiving research papers in Arabic, as it reminded us of the existence of feminist researchers and writers who are able to produce wonderful writings in our language.

The journey of working on this book took place during a year of one major turn after another: the global covid pandemic, the economic and political collapse in Lebanon, the demonstrations and protests that were suppressed with violence, the Beirut port explosion, more protest suppression, impoverishment of people, mass migrations, economic-political scandals, and political assassinations. These crises are so numerous they are hard to capture here. Paradoxically, the more we researched about the nineties, the more we understood the importance of diving deeper into the era in order to understand the reality of today.

In reality, being aware of the importance of learning about our history from a feminist perspective is what pushed us to continue writing, revisiting and revising. We now realize the importance of looking back at past events with temporal distance and with knowledge of the repercussions that led the country to where it is today, and that shaped our reality as feminists, with all our failures and achievements.

The conversations, by Zeinab Dirani

The first time I heard about feminism, its history, and the people who participated in the feminist struggle across past decades was through the Internet. Neither my grandmother nor my mother told me stories about the lives of local women, despite the fact that they constantly shared stories about their lives and history. But I would discover some feminist features in the details of some of their stories. Online search pages indicated to me that feminism “began” in distant countries where I had not lived. The content was written in languages other than mine, and in contexts unfamiliar to me. I was in my early teens when I tried, to the best of my ability, to analyze and visualize the link between these distant contexts and any feminist presence in Lebanon. But the story that I was trying to form wasn’t based on documented information about the history and reality of this country, nor on the stories, history and forms of feminism which I got to know at that time through the feminist waves. Back then, there was no chance for me to know about the existence of other feminist histories and stories, and other frameworks in which to look at feminist history.

But even back then I wanted to understand: What does feminism mean to me? How do I discuss the feminist terms that I read about with my mother or my schoolmates if they are not in our language, and if parts of them do not apply to our geographical, social and class reality, without us clashing and concepts getting mixed up?

There was a whole feminist history in the region that I was unaware of. For there were feminists in this same country, and in the same cities I lived in (Sidon and Beirut), who fought under violent circumstances, through parallel and intertwined hegemonies and occupation; for me, that meant that they worked most of the time under circumstances hostile to feminist presence, to social change endeavors, and to the open discussion of any marginalized issue.

If I knew then that a feminist history unites my mother and I, unites the struggles of past generations and our current struggles, and unites women from distant countries and wider circles, I would have been able to use this history to communicate with my mother and my friends, with other women and with myself, in a better and more constructive way, and in a language we could all understand. We would have been able to draw support from similar past and current experiences and contexts, and recurring patterns would be clarified, so that we could understand how we dealt with them in the past, and what that currently means for us in the way we work and organize.

This is why the entire journey of this book, and all the dialogues and discussions that took place were an important educational stage for me. This is what the intergenerational feminist meeting organized by the Knowledge Workshop in November 2020 represented; this meeting – for me, for the editorial team and hopefully for the attendees as well – was a rare safe space for sharing stories across generations.

We chose to have a closed first meeting (since we wanted this to be the beginning of multiple and more inclusive meetings), in order to maintain a degree of intimacy. For this intergenerational meeting, we invited feminists that we knew or have heard about. We sent out thirteen invitations to individuals who are just getting familiarized with feminist concepts and associations, and to others who have been associated with feminist activism and research for the past three years, ten years, and even thirty years. Some of these people were part of our close circles, and some we were meeting for the first time. In particular, we mention feminist activist Lina Abou-Habib whom we approached with the idea of this meeting. She suggested the names of feminists in different phases of their feminist journey. Lina of course participated in the meeting and encouraged us to hold other similar gatherings. This meeting was also an opportunity for us to share some of the stories we heard while researching feminism in the nineties, and to hear the questions and opinions of young feminists.

And in those two hours that we came together, we listened to many stories and topics from the 1990s. These stories will be repeated extensively and from different perspectives throughout the book, from Beijing to the Aisha Network, the Arab women’s court and the different strategies that feminists have devised to meet the challenges of the time. The feminists who attended the Beijing conference spoke about how they were introduced to new concepts and frameworks for feminist work, and about the challenges of incorporating these concepts into their discourse. It is worth noting that these terminologies and concepts have become fundamental to the feminist discourse in twenty-first century Lebanon.

During the meeting, we heard about the reality of the Palestinian feminist movement in Lebanon— which Leila Al Ali delves into in an interview with Fatima Al Mousawi and Sintia Issa in the publication. We saw how the term “women’s movement” is used as distinguished from the “feminist movement.” In fact, this was the first question that was raised by a young feminist during the meeting. There were also questions about the development of the feminist discourse since the nineties to the present. The meeting opened the door to questions about ensuring the continuity of relations across generations, about how to communicate continuously, without it being an extra burden added to an agenda always oversaturated with urgent obligations. There were also questions about ways to maintain the spirit of collective work that we create when we organize together, and how to derive strength and support from these connections long after an event has ended.

Before the gathering, and during the meeting, we discussed ways to expand the spirit of this intergenerational feminist gathering. We know that it is impossible for a single book or group to cover all the questions and aspects surrounding feminism within a decade; and that meeting, getting acquainted, and sharing experiences and lessons are important practices that enhance our work. We also know that many activists involved or interested in feminist work are neither writers nor researchers, and they therefore have not written down their reflections or testimonials. Finally, our goal in the Knowledge Workshop, through this book, and through our various projects, is to encourage the remembrance and re-exploration of our history and our stories, with the awareness that these stories may be in either harmony or contradiction with the narratives included in this book.

Book Division

In the first chapter, Najwa Sabra writes a love letter to her sister and recalls the songs they grew up with in the nineties. The second chapter presents the story of T., who traveled from Sri Lanka as a teenager during the 1990s. Her story captures the struggles and defiance against racism and injustice, and the everyday encounters of her life in Lebanon. In the third chapter, Mira Tfaily examines the memories of a woman who lived in Beirut during the nineties to think about what a post-conflict city means to her, and how this coincides with the researcher’s assumptions about that era.

Chapter four starts in the present moment, where Reem Joudi bears the grief and anger of 2020, to reflect on the writings of Etel Adnan and the art of Huguette Caland. In her essay “Of Cities, Women, & Bodies: Etel Adnan and Huguette Caland in Conversation,” Joudi creates a conversation between the two artists and communicates with them through her work, reflecting on affiliation, post-war cities, exile and transformation. Researcher Rasha Melhem also discusses Caland in the chapter on Janine Rubeiz’s gallery, as she examines how the gallery supported artists, especially women, during the nineties. In Chapter six, Areej Abou Harb delves into the history of music in the Arab region. She contextualizes the emergence of women singers and actresses in Lebanon and their visions during the video clip era of the 1990s. Researcher Watfa Hamadi follows with an analysis of three plays from the nineties. Through these productions, Hamadi calls attention to the shift in the discourse focused on women, their bodies and sexuality, which she argues was a reflection of a change in feminist discourse in 90s Lebanon.

Chapters eight and nine focus on the socio-economic aspects of women’s lives in Lebanon. Nancy Ghozayel explores the economic situation of four women in Tyre during the nineties. Her research looks at systematic repression and violence, highlighting how Israeli attacks on southern Lebanon aggravated this violence. In chapter nine, Luna Dayekh examines “Sites of Resistance Women’s Activism in Lebanon under Neoliberal Reform in the 1990s.” This chapter narrates the nineties from the point of view of three women activists, revealing how they experienced neoliberal post-war reconstruction, how they resisted gender norms, and how they lived through the sabotaging of movements that sought to find alternatives to this economic and social order.

In chapter ten, the editorial team writes about Wadad Halawani’s story with the Committee of the Families of the Kidnapped and Missing in Lebanon. While in chapter eleven, researchers Fatima Moussawi and Sintia Issa interview the Palestinian feminist activist Leila Al Ali, who remembers the story of Al Najdeh Association and the work of Palestinian and Lebanese feminists during the 1990s.

In the following chapter, Fatima Moussawi captures the many dimensions and different voices of the feminist movement in 1990s Lebanon, ending her research by pointing out some of the issues marginalized by feminists at that time. Mariane Ghattas and Sintia Issa follow in order to fill some of these absences. In Chapter thirteen, Ghattas writes about the context that allowed the turn towards more isolation and erasure of the representation of lesbian and transgender women. Ghattas also showcases the emergence of early voices and safe spaces at the end of the nineties, which ultimately led to the growth of queer activism in the twenty-first century. In chapter fourteen, Sintia Issa narrates the stories of three migrant workers, showing how organizing emerged since the 1980s, at a time of Lebanese feminist silence on this issue, until the creation of more spaces built on inclusion and solidarity in discourse and/or practice.

Chapter fifteen presents yet another testimonial. Myriam Sfeir recalls the time she joined Al-Raida journal shortly after her graduation in 1994. Her story is rich with the details of her exploration of the city and of feminist activities during that decade. In chapter sixteen, entitled “Feminist Consciousness in Nineties Lebanon,” Lina Abou-Habib writes an analysis of the feminist movement in the 1990s, as the movement reassembled itself after long years of civil war. Abou-Habib highlights the ways in which feminist issues and methods of organizing evolved during that decade, despite resistance and attempts at appropriation. She also explains how the Beijing conference and its preparatory meetings contributed to the changes taking place. In chapter seventeen, Azza Chararah Baydoun shares an archival document: a letter from 1995 in which she expresses her thoughts on the preparatory meetings that lead to the “Beijing” conference. Finally, we end the book with the personal reflections of Jean Said Makdisi, who recalls some of her frustrations during her participation in activist efforts to organize after the war. Makdisi thus took the path of exploring the history and lives of women in her family and in her society.

As we were finalizing our work on this publication, we received the painful news of the death of Dr. Watfa Hamadi, with whom we had made wonderful memories while working together on her featured text. We enjoyed and learned from our conversations with her, and we were motivated by her constant encouragement and support. Thank you, Watfa, for everything you have given to the feminist movement. You will always remain in our memories and hearts.

[1] “Jean Said Makdisi,” Knowledge Workshop https://www.alwarsha.org/jean-said-makdisi/

[2] For a publication that explores women and feminism in a much earlier decade, I can point you towards a Bahithat volume on Arab Women in the 1920s: Changing Patterns of Life and Identity (2003).

[3] أبو غزال، سارة. “سبع عبر من العمل النسوي في لبنان” ٢٠١٥ ، صوت النسوة https://sawtalniswa.org/article/471

[4] Fatima al Moussawi clarified this idea of feminists feeling that they needed to forget and do their work as she was reflecting with me on her research interviews.

[5] In 2014, I finished working on my doctoral dissertation, where I had spent a few years trying to assemble and put together a history of feminism in Lebanon, to ground and expand the queer feminist thought and activism of the present. It was at that time that I started searching for a way to tell the story that would disrupt a linear chronology, and would give feminism, and queer feminism especially, a past to feel part of, feel reflected in, and also put us in touch with some of the issues we have to confront. And it was (often queer) Black feminist, indigenous and women of color writings and theorizing, their critiques of waves and theorizing of non-linear temporalities that taught and inspired me the most. Writers, scholars and teachers such as Gloria Anzaldua, M. Jacqui Alexander, Maylei Blackwell, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Okhi Simine Forest and others. I also looked towards structures and ways of storytelling in foundations literature from our region (such as A Thousand and One Nights). Stories and storytellers, ancient and contemporary, have always mobilized non-linear movement of events, with one story making way for others, and returning to one or more points of origin or framing. For more on these frameworks and histories, see “Shadow Feminism in Lebanon”

https://sawtalniswa.org/article/460. See also part 2 of this history in Sawt: https://sawtalniswa.org/article/481

[6] For other examples of scholars use of multi-directional or cyclical temporalities, see also “Memory Studies and the Anthropocene: A Roundtable” in Memory Studies (2017) (thank you, Islam Khatib, for this reference).

[7] Thanks to Hana Sleiman for bringing these observations to my attention as she was reading and commenting on an early draft of a call for papers for this publication. For their contribution and comments on the different calls for this publication, I thank Lamia Moghnie, Sara Abou Ghazal, Aya Hesham and Mira Assaf Kafantaris.

[8] Safaa and Zeinab’s sections in this introduction are translated by Lea Sbaite